Photo by jronaldlee.com

Photo by jronaldlee.com

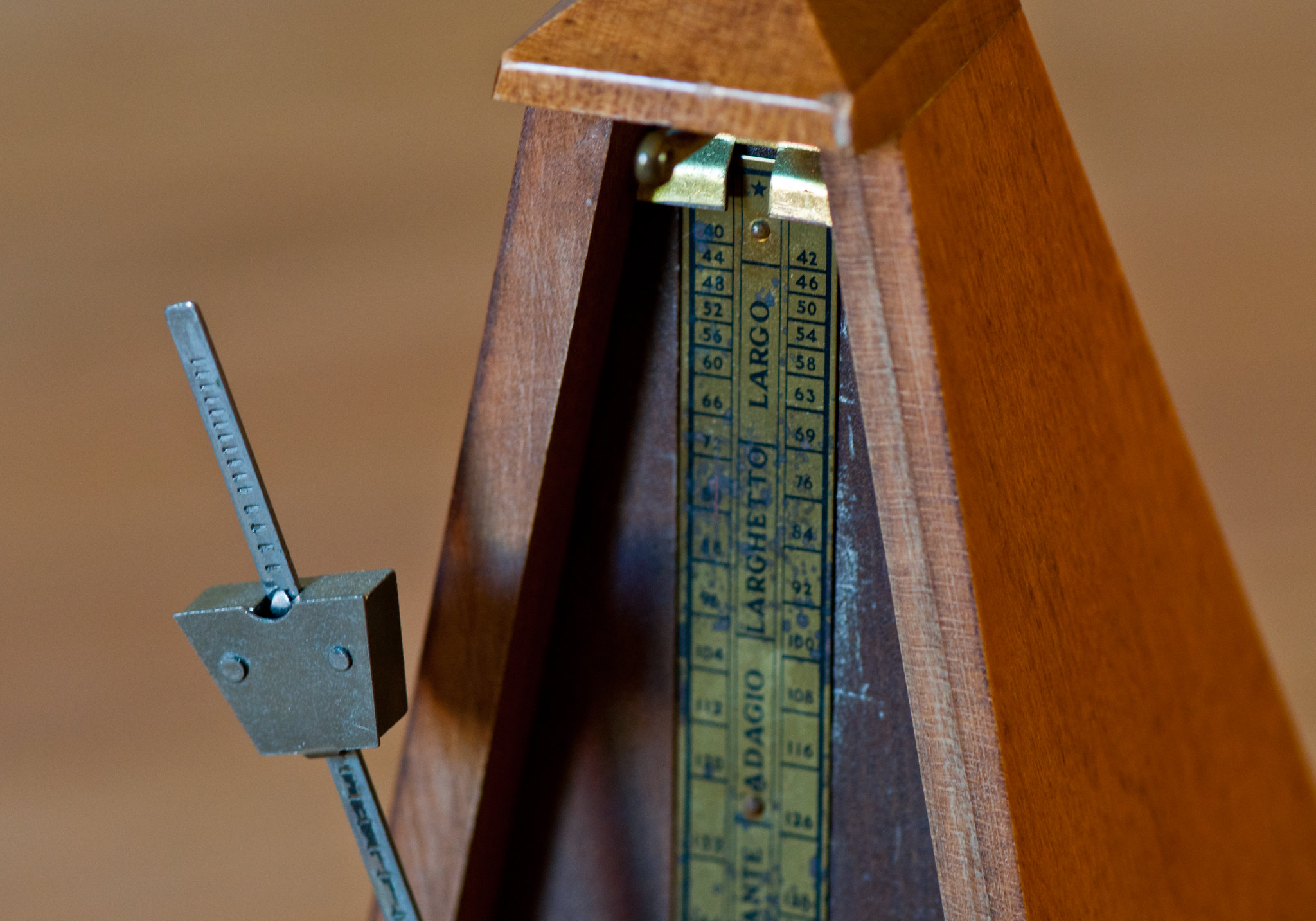

I always wanted to play the piano, but lessons seemed so boring—play the same simple dull piece over and over, I’d much rather play something good, and figure it out on my own! If I can play something more complicated, why would I want to waste time with the simple stuff?

So I did that for a while; I’d listen to a song, figure it out, play it over and over until I got it. I sounded reasonably good to someone who didn’t know better. But when I tried to learn something more complicated, push myself to the next level, I hit an immediate and immovable wall. No matter how hard I practiced, I couldn’t pick it up. My brain knew what I wanted to do, but my hands wouldn’t cooperate.

I was missing an entire massive foundation of skills and skipping right to the output. The muscle memory, the posture and theory. Scales and arpeggios, rhythms and dynamics. Modes, transitions, standard phrases. I didn’t have any of it to use.

Piano teachers will roll their eyes when you try to skip the basics—and it’s with good reason. The basics work, and they have for a long time, refined carefully and intentionally over literal actual centuries. You can’t short circuit that with some quick youtube and memorization. If you go rogue, you’ll hit a wall that will often require unlearning bad habits before making forward progress.

Modern AI development tooling brings this risk pattern front and center in software development. The tools that we’re rushing to get into the hands of developers make it trivially easy to skip the fundamentals and go straight to the output. But like my playing a song based on some Synthesia piano tutorial I found on Youtube, there are costs to jumping ahead without the base layer of understanding firmly locked down.

The Irresistable Call of AI Tooling

AI tools today can scaffold projects, debug code, and write tests at unprecedented speed. In experienced hands, they multiply productivity massively. But as we build the next generation of engineers with these tools, how do they learn fundamentals necessary to use the tools effectively, if we’ve delegated away the execution?

The pipeline that once slowly shaped problem-solvers through repetition and refinement now risks producing operators of tools—not architects of systems.

What We’re Losing

Instead of learning through the grind of debugging and iteration, it’s now possible for early-career developers to create impressive looking output instantly—often without fully grasping any of the implementation details.

It’s trivial to ship code that works superficially, but can they explain why it works? Can they reason through edge cases, scalability, or failure modes? When things break, do they know how to trace the fault?

Unchecked, these tools can be massive technical debt generators, layering oft misguided or unnecessary complexity with inconsistent and difficult to maintain patterns, security holes, and disjointed repetition.

You start to see the symptoms:

- Projects stall when the tooling can no longer adequately reason about the complexity, and the developer is unable to unwind it or guide it. Large parts of functionality start to regress with new features.

- Code reviews where contributors can’t explain what their code actually does, or may not have even seen or considered the code prior to the review.

- Projects that seem to make massive quick progress, but disintegrate when the rubber hits the road on non-trivial requirements.

- Systems that are either dangerously naive or bloated with abstractions and complexity not grounded to a real requirement or mitigation.

Some of these may pass silently, charged to the Technical Debt Credit Card for later payment, while the bigger and louder issues will derail and disrupt projects outright.

Intentional Friction

While a seasoned engineer may have the background and knowledge base to avoid these pitfalls, early-career engineers most likely do not, and unguided or unchecked, AI tooling represents a big invitation to avoid their consideration altogether.

Learning these fundamental principals becomes much more difficult the higher the level of abstraction. We need to both setup a development structure that encourages the building of these base layer skills, and identify and correct the risky practices before they become embedded or fail.

Twinkle-twinkle before La Campanella. Before pushing toward the high-powered tools, encourage early-career developers to build things the hard way. Create an environment where slow intentionality is re-enforced at the early career levels. Help them wrestle with error messages, trace bugs by hand, write code from scratch. Drill the scales and arpeggios. Then, phase in AI deliberately while they progress:

- Start with basic autocomplete and Q&A tools.

- Advance to cut-and-paste snippets that require understanding and adaptation.

- Move to integrated assistants that offer suggestions—but still require human steering.

- Graduate to agentic systems only once foundational judgment is already in place.

All along, we should be having conversations about justification. Ask: Why this approach? What trade-offs did you consider? What breaks if your assumptions are wrong? The feedback loop is especially important, as much of this tooling can create output that may successfully produce the desired outcome superficially, with significant hidden costs both to the codebase and the developer’s level of understanding.

As leaders, we need to be the piano teachers. Encourage fundamentals first. Work slow. Give the structure in which to improve these skills without skipping to the output by creating an environment with a progression of intentional learning—supported by level-appropriate friction and speed.

Foundations then Fluency

“Slow down! The speed will follow,” my piano teacher would say when I rushed ahead of my skills.

Like music, software has structure. A pianist can’t fake complex passages without foundational technique, and developers can’t reason about systems they never learned to construct. Skip the foundation, and they can’t explain why something works, fix it when it breaks, or know when not to build it at all.

We can’t just hand over the tools and hope for the best. We must create environments where foundational learning is expected and supported with intentional friction. That means guiding appropriate tool use, helping with evaluation, and giving space for struggle.

If we want engineers who can design, adapt, and lead—not just copy, paste, and prompt—we need to give them room to learn the scales, make mistakes, and build the muscle memory of understanding why beneath the what.