What makes a Senior Developer? A Staff Engineer? An Architect?

“Why do you ask?” I’ll probe, and the result is often revealing: “I want to know how to get to the next level.” or “I’m wondering if I’m ready to be a Senior.”

Fair questions. Career growth matters. And understanding how it’s measured can help. But if you treat your path solely like a clean, stepwise ladder—title after title—you risk missing what actually builds value: the skills, insight, and judgment that emerge from the messy, unpredictable edges.

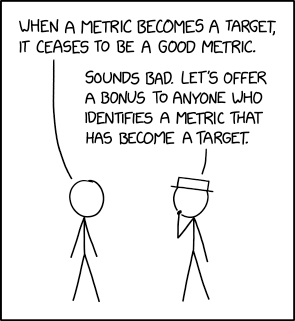

Goodhart’s Law: When a metric becomes a target, it ceases to be a good metric. Or more casually: “If you make a game, people will play it.”

We love structure. Volunteer—it looks good on college apps. Land the right internship. Convert it. Pick the right company. Junior > Dev > Senior. Strategic move. Staff > Principal > Manager > Director. No gaps—people might wonder.

The reality is that “messy” careers, those that don’t follow a careful expected choreography, are often an indicator of something very important: curiosity. And having an active and developed curiosity is a massive distinct advantage, especially in any field that aims to solve problems, which is, well, most of them.

Wait, we’re all woodworkers?!

I was once seated at a conference table during a break at a long requirements gathering session for a project. The group was mostly talented technical people in a variety of domains. Making small talk, someone mentioned that they were a woodworker. One by one, people all around the table revealed that they too were a woodworker, and added some context about their shop, tools, etc. The group laughed awkwardly as each additional person chimed in with their bit of unexpected common thread.

The phenomenon makes sense: in woodworking there are endless challenges and aspects to explore. You get to both build something and always be learning or trying some new aspect. You get to try, fail, and improve. The feedback loop is quick and very real. In total: it feeds curiosity. And talented engineers more often than not are curious folks.

This wasn’t just a funny coincidence. It was a room full of people whose curiosity doesn’t stop at work. Their instinct to explore, build, and solve problems shows up everywhere—including their careers. This curiosity is not just a trait shared by good engineers, it’s what makes them good engineers.

The Book of Rhymes

There’s a saying: History doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes. Experience works similarly.

The more problems you solve, the more familiar they begin to feel. Different industries, different projects—but underneath, the same core themes appear again and again.

That’s your “book of rhymes.” It’s a collection of mental patterns—past successes, close calls, and hard-won lessons that guide your judgment.

It’s not trivia. It’s about recognizing the familiar: deadlines that slip, risks that escalate, shortcuts that backfire. The more varied your domains and experiences, the more dense and useful your book becomes. A cross-domain rhyme is the best kind.

And this is where curiosity pays off. Every detour, every side project, every strange challenge you take on builds that book. Curiosity isn’t just a way to explore new things—it’s how you gather the raw material for future insight.

But I’m Just Not That Curious

Curiosity isn’t a fixed thing you either have or don’t—it’s a muscle that strengthens with use. And you can purposefully exercise it.

Adjacent problems. Look at the edges of what you’re already doing. If you’re focused on frontend work, what happens in the backend when your requests arrive? How might Infosec think about this problem? If you usually work on features, what does the deployment process look like? What’s really important to a PM? Small steps into neighboring territory.

Ask “why” more often. When something breaks, don’t just stop at the symptom and resolution, understand the root of the behavior. When you see a pattern, dig into why it emerged. The “why” questions are curiosity’s starting point.

Give yourself a purposeful 15 minutes. When you encounter something you don’t understand, spend 15 minutes exploring it. Not to master it, just to poke around. You’re not committing to becoming an expert—you’re just satisfying that tiny spark of “I wonder what this is about.”

Talk to people who work in different domains Ask the sales team what they’re hearing from customers. Find out what the support team’s most common issues are. Ask the networking team how they handle something interesting. Different domains reveal different problems, and different problems expand your pattern recognition.

Say yes to the weird requests. That Lotus Notes migration project. The weird integration with that legacy system. The prototype for the marketing team. These aren’t distractions—they’re opportunities to add new high-value pages to your book of rhymes.

Each small exploration makes the next one easier.

The Ladder is Optional

It’s fine to think about titles and levels—they exist for a reason. But a funny thing happens when you let your curiosity lead: the path forward—though organic and meandering—tends to reveal itself. You don’t need to obsess over career positioning or navigate some complicated choreography. When you’re consistently learning, solving interesting problems, and following what genuinely sparks your interest, the right opportunities tend to show up.

The best engineers I know didn’t get there by playing the ladder game. They got there by staying curious, trying odd things, and learning from every messy step along the way. In the process, they ended up producing results that couldn’t be ignored.

And if you’re leading teams or working with talent, it’s worth remembering: those “messy” career histories—full of detours, gaps, and unusual projects—are often where your most adaptable, resourceful people come from. The ones with the broadest books of rhyme are usually the ones who quietly solve the hardest problems.